The Sand Creek Massacre

Date: November 29, 1864

Location: Sand Creek, Colorado Territory

In 1851, seven Native American tribes, among them the Arapaho and Cheyenne, signed the Treaty of Fort Laramie, which recognized their rights to an extensive territory encompassing the entirety of Wyoming, and large parts of Kansas, Colorado, and Nebraska. Following the Pikes Peak Gold Rush of 1858, hordes of American colonizers began encroaching onto their land, establishing illegal mining camps, getting into fights with the native peoples, and stealing tribal resources and livestock.

Prospectors in the Rocky Mountains c. 1858

As the US increased their military presence surrounding the tribal reserve, the Bureau of Indian affairs proposed a new treaty. This treaty, the Treaty of Fort Wise, shrank the tribal lands to about 1/13th the size proposed in the Treaty of Fort Laramie and relegated the Arapaho and Cheyenne in particular to a small reserve in eastern Colorado. The chiefs, fearing the repercussions of what would happen to their people should they refuse to sign, signed the treaty on February 18, 1861.

The Arapaho and Cheyenne were outraged, with many believing that their leaders were either coerced, misled, or bribed to get them to sign such a humiliating document. Tensions rose, and many bands refused to recognize the new borders and continued to hunt, fish, and forage in the lands originally promised to them. As more and more settlers poured into their former lands, these bands began raiding and engaging in small skirmishes with the settlers, but these confrontations grew in size, scale, and regularity following the outbreak of the American Civil War in April 9, 1861. With the Union forces stationed in Colorado being sent south, and too preoccupied with battling the Confederates for control of the New Mexico Territory and the Arizona Territory, the tribes launched offensives against forts and settlements throughout the region, with much success.

Colorado Territorial Governor John Evans

By 1863, the conflict on the plains had grown to such a fevered pitch that Colorado Territorial Governor John Evans was urged by the Bureau of Indian Affairs to meet and negotiate the Arapaho and Cheyenne. Both sides attempted peace talks that ultimately failed to come to fruition. By early 1864, the Arapaho and Cheyenne had formed a coalition with the Comanche, Apache, Kiowa, and Sioux to purge the colonizers from their land once and for all, turning huge swathes of the American West, already drenched from the bloodbath of the Civil War, further into a warzone.

Photograph of Arapaho and Cheyenne leaders who met with Governor John Evans, taken approximately two months before the Sand Creek Massacre. Captain Silas Soule is in the foreground, on the right.

On June 27 1864, Territorial Governor John Evans invited the tribes to gather at Fort Lyons on the eastern plains of Colorado and promised protection for the tribes that came, not seeking to end the carnage that was now in its third year, but rather separate and guard the bands at Fort Lyon that preferred peace, and continue to fight against the remaining bands that preferred war. In September, Chief Black Kettle and Ochinee led nearly two hundred Cheyenne to Fort Lyon, later joined in November by Chiefs Little Raven and Niwot leading several hundred Arapaho. Shortly afterwards, allegedly for their safety, the US Army ordered the Cheyenne and Arapaho at Fort Lyon to relocate to a reservation 40 miles northwest of Fort Lyon, at Big Sandy Creek. Black Kettle, Ochinee, Niwot and other leaders refused, pleading with the army that their people there were mostly women, children, and the elderly and would not survive a march through the snow and ice of the Colorado high plains. To show his dedication to peace, and as a desperate appeal, Black Kettle flew the US flag above a white flag on his dwelling.

Southern Cheyenne Chief Black Kettle & Colonel John M. Chivington

On November 28th, the 425 troopers of the 3rd Colorado Cavalry, led by Colonel John M. Chivington arrived at Fort Lyon, and he assumed command of the forces stationed at the fort, the 1st Colorado Cavalry and 1st New Mexico Volunteer Infantry. Chivington, who back in 1862 played a key role in the decisive defeat of the Confederate invasion of the New Mexico Territory at the Battle of Glorieta Pass, had since been involved in the various wars and conflicts with tribes. After years of fighting in small skirmishes and ambushes, he sought to relive his glory days at Glorieta and fight victoriously in another major battle, one that could help him attain a higher rank in the military or even begin a potential political career. The 100-day enlistments of the entire 3rd Colorado, and thus his command position, was set to expire before the end of the year, and so this window of opportunity for this exaltation Chivington so desperately craved grew more urgent by the day.

On the frosty morning of November 29, 1864, Chivington led his forces to the encampment, and ordered an attack. Two companies of the 1st Colorado and their officers, Captain Silas Soule and Lieutenant Joseph Cramer, refused to obey the order.

The remainder of Chivington's forces charged forward, guns blazing, into the encampment full of mostly women, children, and the elderly, still flying the US flag over the white flag of surrender.

Multiple firsthand accounts describe the sickening and deeply disturbing nature of the massacre that followed. Unarmed men, women, children, infants, and the elderly were cut down by bullets, artillery fire, and swords where they stood or while they attempted to flee the horror. The soldiers mutilated the living and dead, slicing off pieces from their bodies as trophies. A few Cheyenne and Arapaho were able to get a hold of weapons and return fire as they desperately fled up the Sand Creek, with cannon fire cutting many of them down.

Approximately 600 Cheyenne and Arapaho were murdered that morning, according to Chivington's own account, though the exact number is disputed and likely less. About 4 soldiers were killed and 21 were wounded, though many were reportedly inebriated by the time the attack commenced and several of these casualties were instances of friendly fire.

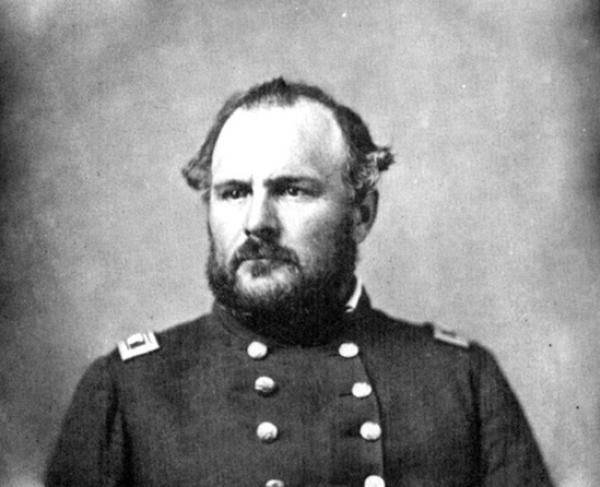

Colonel Samuel F. Tappan & Captain Silas Soule

The news of the massacre at Sand Creek sent shockwaves across the country. The public, the military, and the government were horrified. Numerous Union veterans of the New Mexico and Arizona campaigns of the American Civil War, many still fighting against the Confederacy as the war raged on in the east, or fighting in the tribal conflicts in the territory, denounced the massacre and Chivington. Colonel Samuel F. Tappan, who had fought alongside Chivington at Glorieta Pass, with Captain Silas Soule and Lieutenant Joseph Cramer, who had served with Chivington and refused to follow his order to attack, all testified against him before a US Congressional hearing. Chivington resigned from the US Army in 1865, before he could face disciplinary charges, and due to the postwar amnesty, avoided any criminal charges.

The massacre completely destabilized the Cheyenne and Arapaho, with both tribes losing so many of their people and tribal leaders. As those killed at Sand Creek were bands seeking peace with the US, the massacre confirmed in the eyes of many that peace, harmony, and coexistence with the US was not possible, and never was. The brutal, endless wars between the US and the Arapaho, Cheyenne, Comanche, Apache, Kiowa, and Sioux on the plains and deserts of the American West were entering their fourth year in 1865, with no end in sight.

"My shame is as big as the Earth. I once thought that I was the only man that persevered to be the friend of the white man, but it is hard for me to believe the white man anymore."

- Chief Black Kettle

A survivor of the Sand Creek Massacre

Comments